The Science of Benthos

Benthos is based on the science of coral reefs. As part of our research on the Global Coral Microbiome Project, which surveys the types of microbes on corals around the world, we wanted to design a game that could give the feeling of how reef ecology microbiology, and human impacts interact. Each card was designed to reflect real interactions documented by reef science.

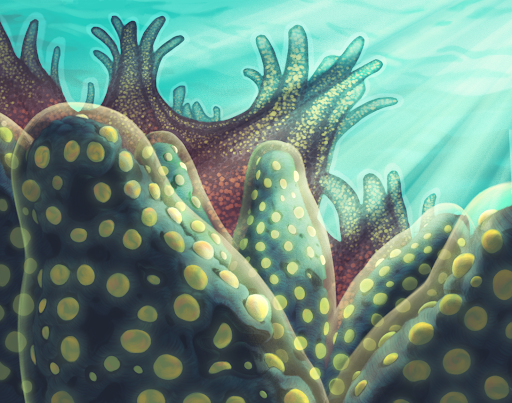

Corals are Animals Powered by Symbiosis and Sunlight

Corals are animals. Unlike most animals, stony corals have microbes called Symbiodineaceae inside their cells. You may hear these referred to as coral symbionts, algae, zooxanthellae, or Symbiodinium. Reef scientists now know that these symbionts are a diverse group of dinoflagellates that form a whole family called Symbiodineaceae. These Symbiodineaceae make energy for the corals by harvesting light. Some seem to be better at making a lot of energy for the coral, while others appear to be better at maintaining symbiosis with corals at high temperatures.

Corals and Algae Compete

Many scientists think corals and macroalgae ("big algae" or seaweeds) compete for space on coral reefs. This competition can take many forms. For example, some experiments show that coral larvae can't settle down onto the reef as well if macroalgae are nearby. Others suggest that toxins from macroalgae may poison corals. Still others indicate that by shading corals, macroalgae may stop their Symbiodineaceae symbionts from gathering energy from sunlight as efficiently.

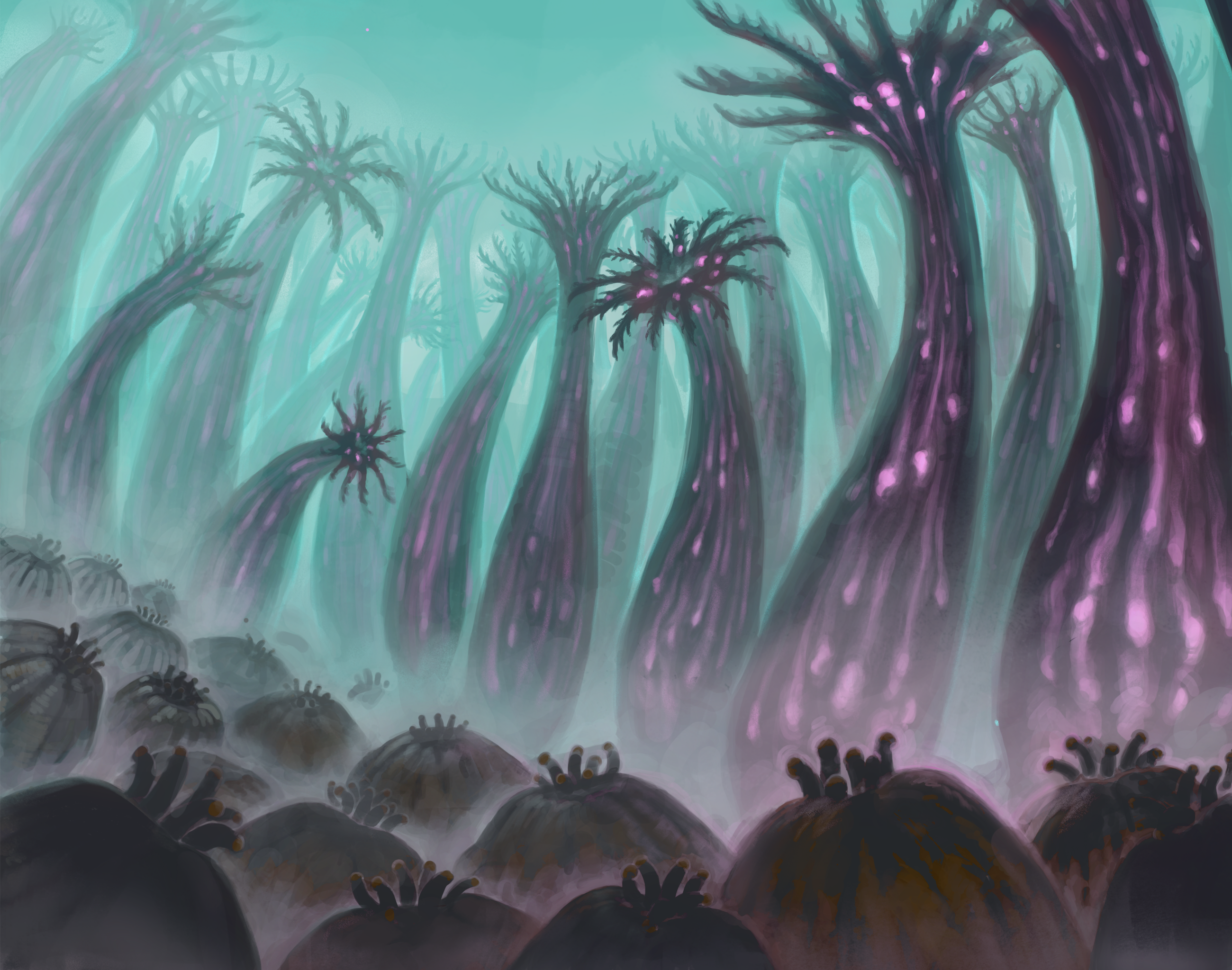

Corals are Ancient and Diverse

One reason we are so interested in corals is that they are an ancient, highly diverse group of animals. Of course, every living creature is just as 'modern' as any other, but corals as a group have been diversifying (splitting into different species) for far longer than flowering plants or placental mammals. The earliest coral fossils stretch back nearly 500 million years, while stony corals like we see today are as old as 250 million years. In contrast, flowering plants (Angiosperms) are about 120 million years old, and placental mammals are only about 80 million years old.

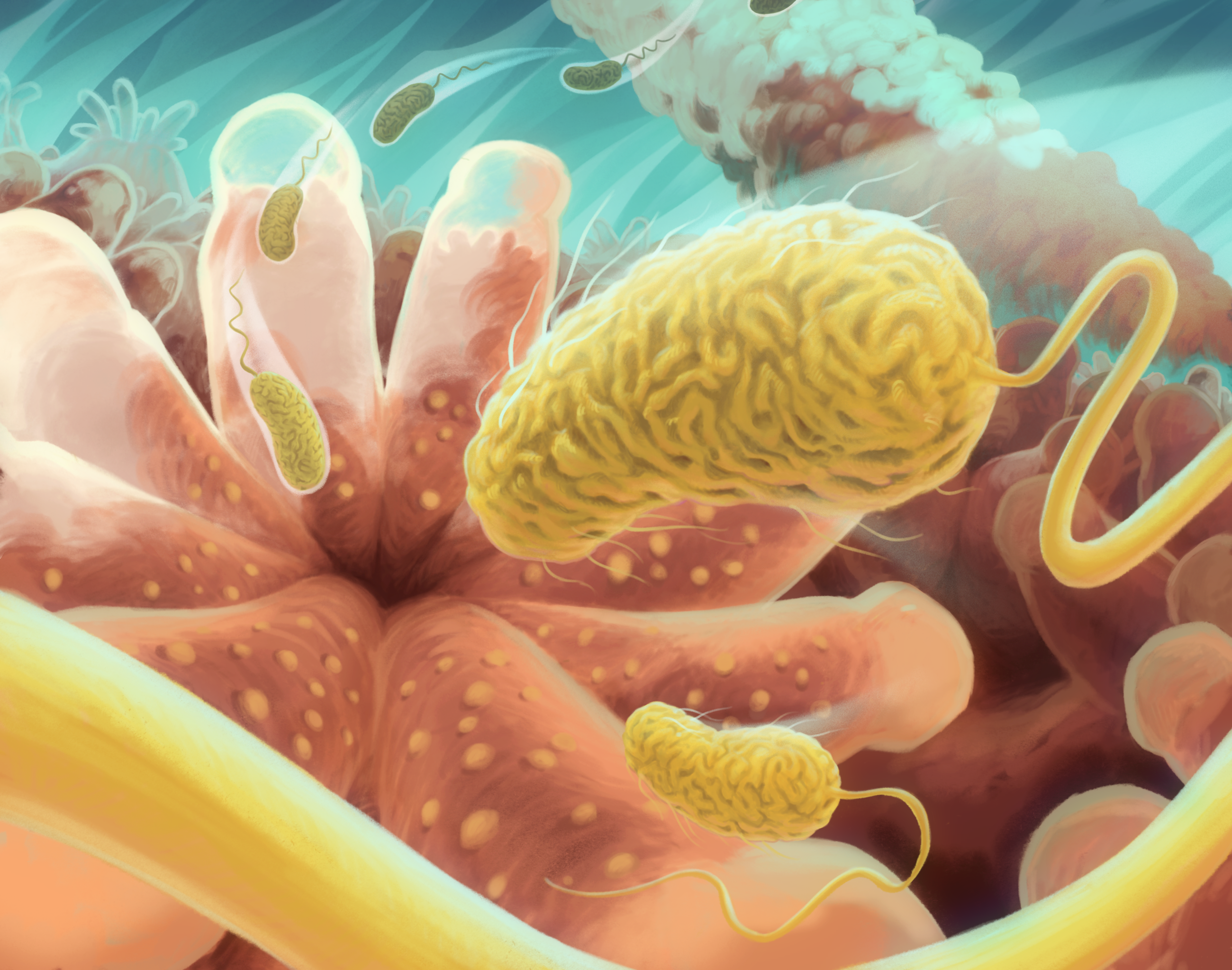

Corals and Microbes evolved together

All of this animal diversity is tiny compared to the diversity of microorganisms. All animal species alive today evolved in the context of immense microbial diversity. Most animals are associated with a microbiome - a community of microorganisms and their associated genes. Many of these microbiomes have been shown to influence important properties of animals - what foods they can digest, their ability to fend off disease-causing pathogens, and how their immune system develops. Some have even been shown to influence complex behaviors like mate choice!

Tradeoffs and the Microbiome

One idea that researchers are exploring is whether symbiosis with microbes can lead to tradeoffs in animal or plant traits. For example, in comparing microbes and disease susceptibility among coral species, the Global Coral Microbiome Project found that coral species with more of a group of bacteria called Endozoicomonas living in their tissues grew faster than other corals. However, they also tended to more commonly develop disease. Current research aims to confirm in the laboratory whether Endozoicomonas really causes faster growth under good conditions but greater vulnerability when a coral is attacked by disease.

Human Impacts Threaten Reefs

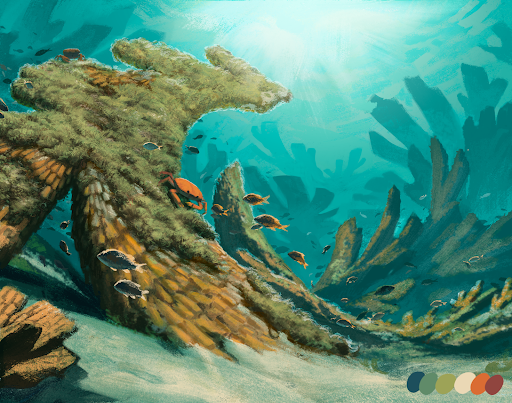

Demographic, technological and economic changes in the Caribbean, mostly after colonization, have produced multiple threats to the ancient diversity of coral reefs and their microbial symbionts at local scales. To understand these threats, we have to return to talking about some of the factors that influence the competition for space on the benthos between corals and macroalgae.

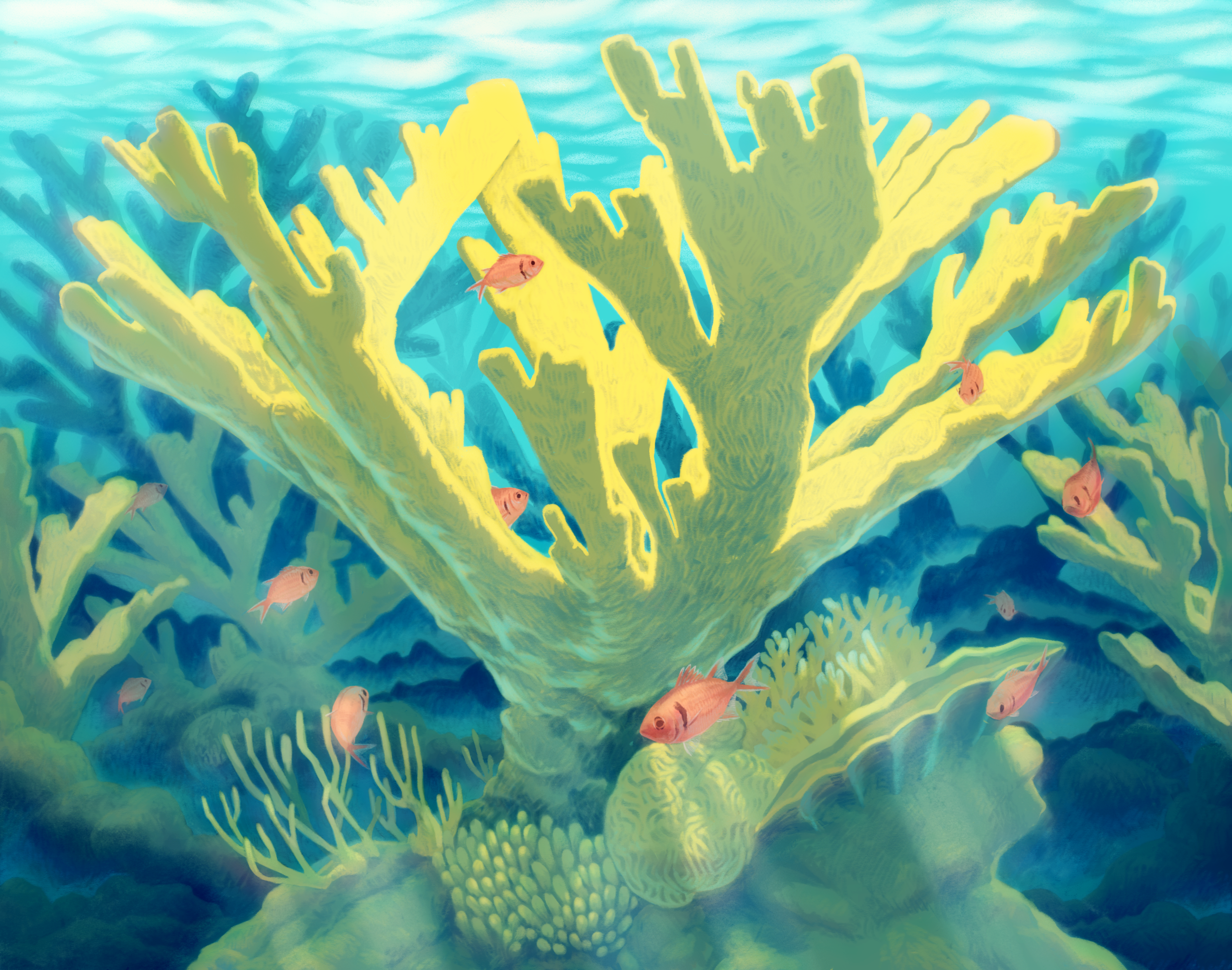

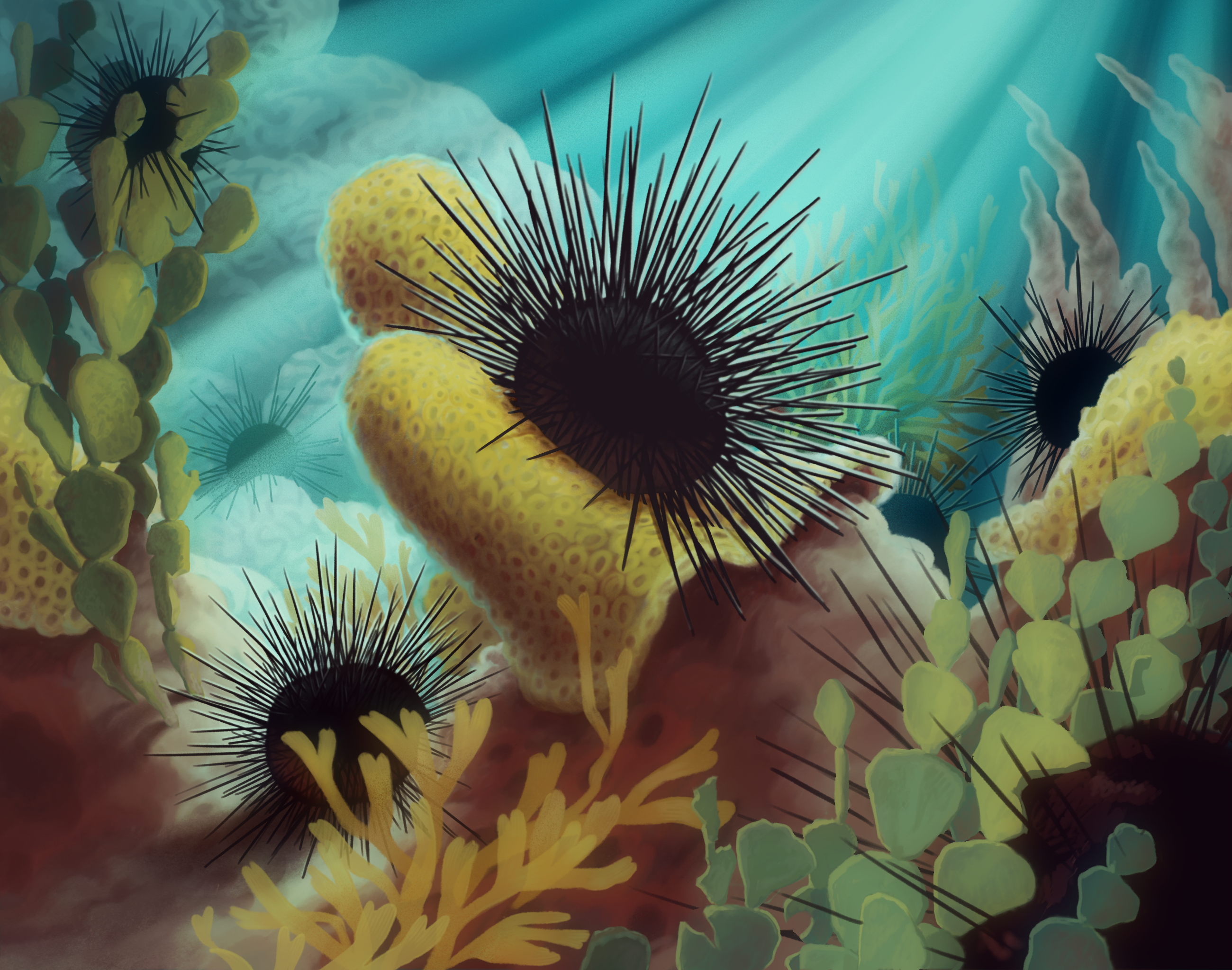

On Healthy Reefs, Living Lawnmowers devour Algae

Before the 1980s, great mobs of black-spined Diadema urchins were a common sight on Caribbean reefs. These urchins scoured algae from the reef, clearing space for vast thickets of Elkhorn and Staghorn corals to flourish. However, in the mid-1980s Diadema urchins began dying in mass numbers from a mysterious disease. The cause has never been definitively worked out. However, recent research on a similar outbreak suggests that a ciliate from genus Philaster is the cause of this disease. This die-off of one of the reef's key living lawnmowers set in motion a chain of events that transformed many reefs in the region.

Overfishing can Remove Key Algae-eating Animals like Parrotfish

While replenishing nearby fisheries is one of many benefits of coral reefs, excessive harvesting of herbivorous fish like parrotfish can mean there are fewer 'living lawnmowers' grazing on algae, and therefore allow macroalgae to overgrow the reef, much like the die-off of Diadema urchins did.

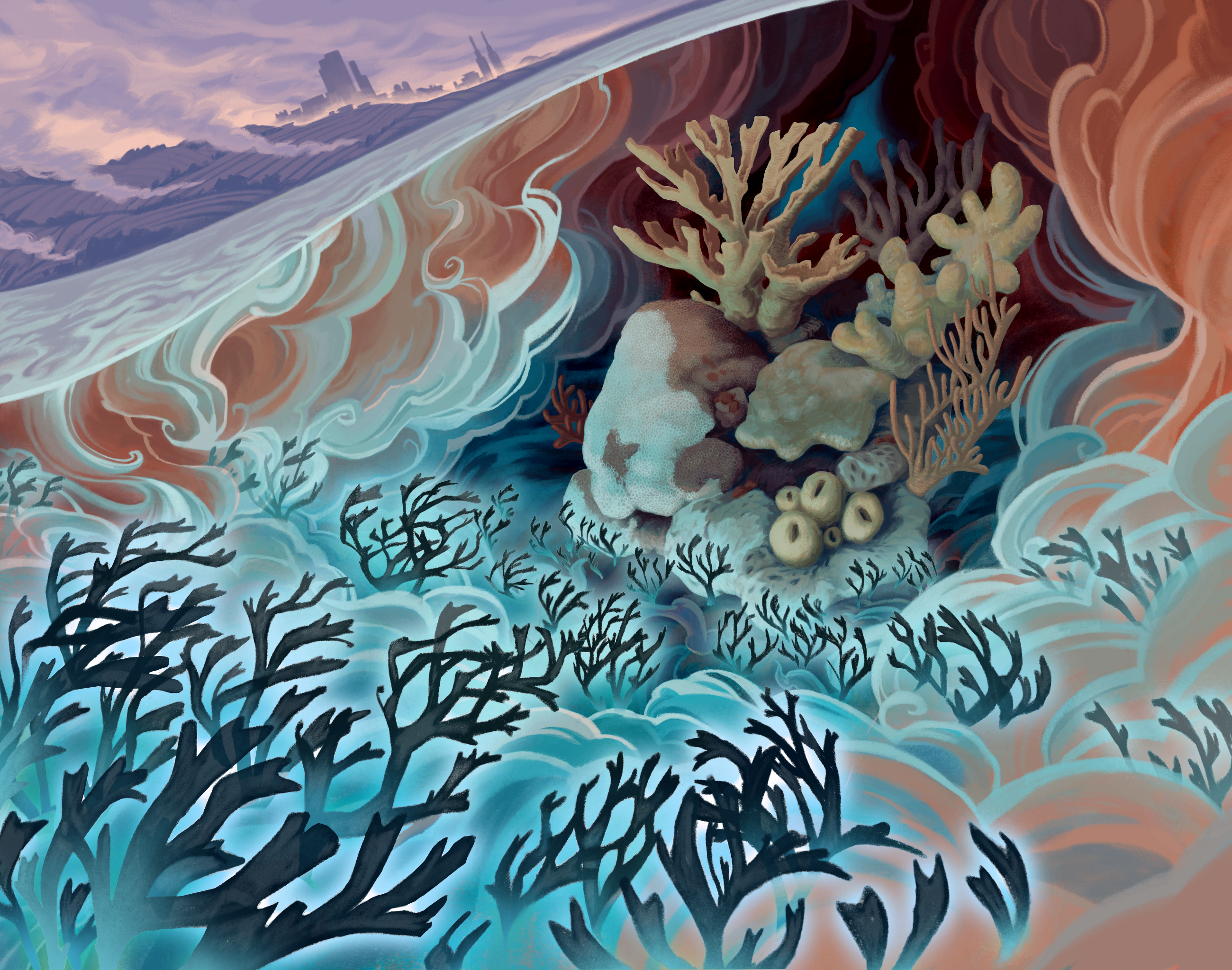

Phase shifts transform reefs

Scientists suspect that at least some features of reefs are self-perpetuating. When coral almost entirely dominate a reef, it can be hard for large macroalgae to find room to establish. This is true to an even greater extent on algae-dominated reefs, where corals struggle to find open spaces in which to reestablish themselves. So on many reefs, disturbances that clear areas of reef can shake up the order of things. A classical example of this is Hurricane Allen's strike on Discovery Bay in Jamaica in 1980. This destroyed many Acropora corals in shallow water. The reef began to recover, with urchins taking over grazing algae from parrotfish that had been depleted by overfishing — but when Diadema urchins died off due to disease between 1980-1983 , the entire reef dramatically shifted from coral to macroalgal dominance — an ecosystem transformation that ecologists call a phase shift.

Nutrient Pollution can Fertilize Algae

Just as fertilizers can make our vegetables grow faster, so too can nutrients running off into the ocean sometimes favor growth of macroalgae. The exact effects can depend on the type of fertilizer and the ecology of the reef, but often greatly stimulate the growth of macroalgae. This is thought to help them better compete for open space on the reef against coral and other reef organisms.

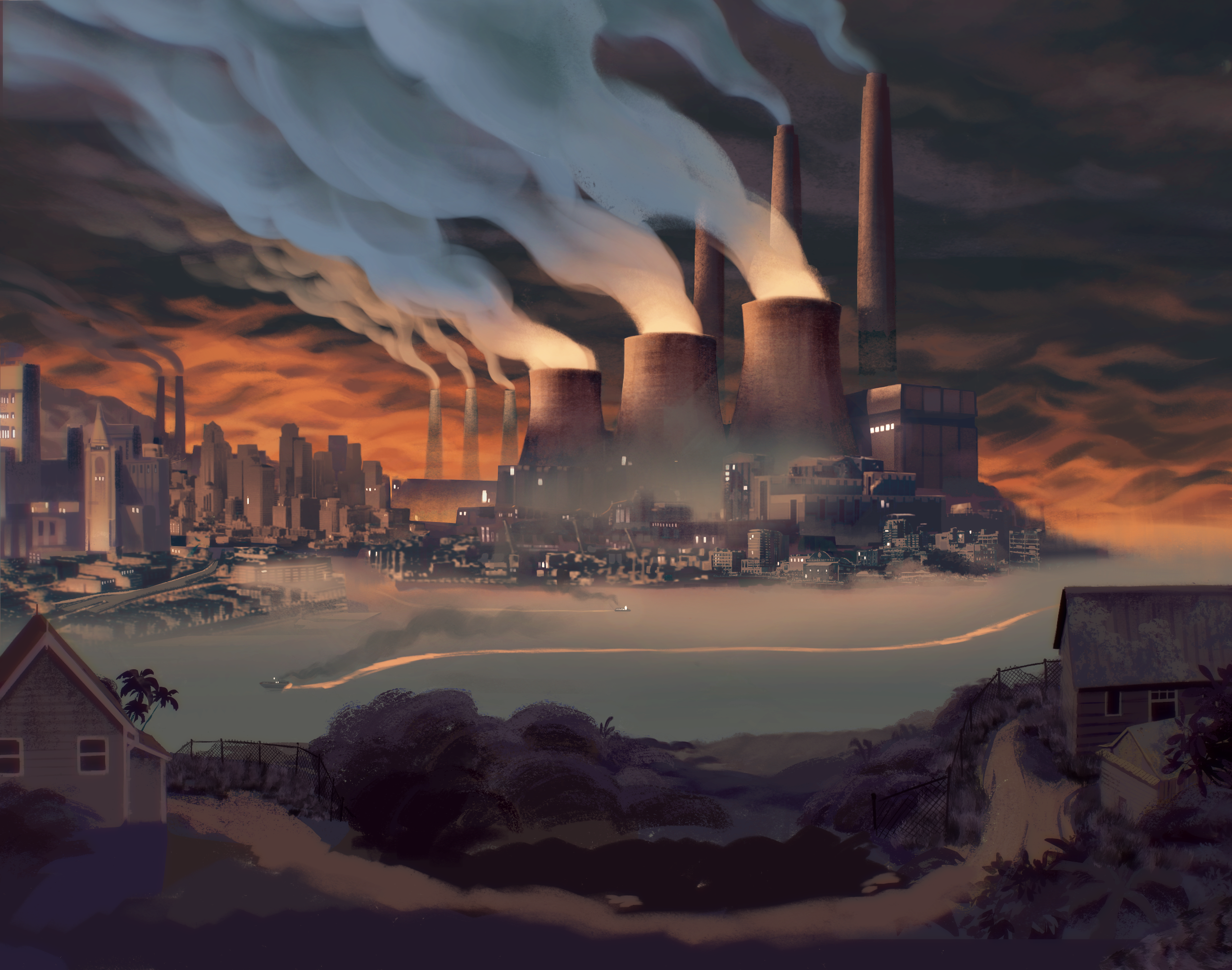

Carbon pollution threatens corals globally

Even the most pristine reef can be threatened by global pollution from CO2 and methane. Coal power has been one major driver of emissions for these 'greenhouse gasses'. By trapping heat in the atmosphere, carbon pollution shifts the climate over reefs. That doesn't mean there aren't cold days - but that on average days are warmer, and periods of extreme heat last longer. The effects of this human-driven change in the climate far exceed natural variation due to things like sunspots - and once carbon is in the atmosphere in immense quantities it is very difficult or impossible to remove it all. Although many island nations produce few carbon emissions, they still suffer the effects of carbon pollution.

Mass Coral Bleaching Disrupts Coral Symbiosis and Starves Corals

During extended periods of high temperature, coral's Symbiodineaceae symbionts become a liability. This is thought to be because they produce harmful free radicals while running photosynthesis. To protect themselves, corals expel or sometimes even eat their symbionts. That solves the free radical problem, but also leaves corals starving and more vulnerable to disease. The exact amount of energy corals lose when they undergo bleaching varies by species and location, but can be anywhere from 30 - 90% of their usual energy intake. Worse, this bleaching covers such large areas that solutions that could make a difference on a very small scale (like pumps to raise up cooler water from deeper in the ocean) do little to protect corals overall.

Local Activism can Make Big Changes

While ideally policy would respond quickly to scientific findings and community input showing that global carbon pollution, and local overfishing and nutrient pollution harm corals and damage sustainable fisheries. In reality, it often takes a lot of loud, creative, messy activism to make change. The good news is that because many local politicians receive relatively little input or interest from the public, even a small group of informed, committed folks who want evidence-based policy can make a difference. This kind of local activism is driving cities and towns worldwide to adopt policies that reduce carbon emissions, improve quality of life, and protect reefs.

Large, well-enforced Marine Protected Areas can protect Fish and Corals

One solution to local stressors like overfishing is to designate large and well-enforced Marine Protected Areas. In these areas, fishing is usually forbidden, allowing populations to recover and supply fish to surrounding areas. Water quality montitoring may also be used to prevent land-based nutrient pollution. These restrictions tend to work best with strong enforcement and buy-in from local communities.

A Race to Radically Decarbonize

Because carbon pollution has long-term effects on climate that are difficult to reverse, there is a race against time to decarbonize global economies. Thankfully, as green technologies scale up, many are proving to be both more cost-effective and socially beneficial. For example, switching from coal to solar power can both save money long term, invest a greater portion of money spent in jobs rather than infrastructure, and save thousands of birds killed each year from coal pollution. Similarly, fast and free or cheap public transit can both reduce pollution and create more car-free public spaces.